Suche

Lesesoftware

Info / Kontakt

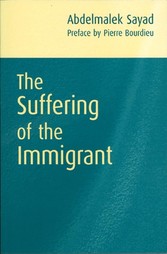

The Suffering of the Immigrant

von: Abdelmalek Sayad

Polity, 2018

ISBN: 9781509534043 , 160 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: DRM

Preis: 26,99 EUR

eBook anfordern

Preface

It was a long time ago that Abdelmalek Sayad conceived the project of bringing together in a synthetic work all the analyses he had presented, in lectures or scattered articles, of emigration and immigration – two words which, as he never ceased to recall, refer to two sets of things that are completely different but indissociable, and which must at all costs be considered together. He wished me to be associated with his project from the outset. In one of the most difficult moments of his difficult life – we had lost count of the number of days he had spent in hospital and of the operations he had undergone – and on the eve of a very dangerous surgical intervention, he reminded me of this project in a serious tone we rarely used between ourselves. A few months earlier, he had entrusted me with a set of texts, some already published and some unpublished, together with suggestions – a plan, outline questions and notes – so that I could, as I had already done so many times before, read and revise them with a view to publication. I should have set to work at once – and I often regretted that I did not do so when I found myself having to justify, alone, certain difficult choices. But Abdelmalek Sayad had survived so many ordeals in the past that it seemed to us that he would live for ever. I was, however, able to discuss with him certain basic courses of action, and especially the decision to produce a coherent book centred on the essential texts, rather than to publish everything as it stood. In the course of our last meetings (and nothing cheered him up more than our working conversations), I was also able to show him several of the texts I had reworked, and which I had sometimes changed considerably, mainly in order to cut the repetitions involved in bringing them together and integrating them into the logic of the whole, and also to rid them of those stylistic infelicities and complexities which, whilst necessary or tolerable in publications intended for the academic world, were no longer appropriate in a book that had to be made as accessible as possible, especially to those it talked about, for whom it was primarily intended and to whom it was in a sense dedicated.

As I pursued my reading of these texts, some of which I knew well and some of which I was discovering for the first time, I could see the emergence of the exemplary figure of the committed scientist who, although weakened and hindered by illness, could still find the courage and strength needed to meet, to the end and in such a difficult domain, all the demands of the sociologist’s profession. He was able to do so only because of his absolute commitment to his mission (not that he would have liked that big word) to investigate and bear witness. His commitment was based upon his active solidarity with those he was taking as his object. What may have looked like an obsession with work – even during his stays in hospital, he never stopped investigating and writing – was in fact a humble and total commitment to a career in public service, which he saw as a privilege and a duty (so much so that, in putting the final touches to this book, I had the feeling that I was not only fulfilling a duty to a friend but also making a small contribution to a lifetime’s work devoted to the understanding of a tragically difficult and urgent problem).

This commitment, which was much deeper than any profession of political faith, was, I think, rooted in both a personal and an affective involvement in the existence and experience of immigrants. Having himself experienced both emigration and immigration, in which he was still involved thanks to a thousand ties of kinship and friendship, Abdelmalek Sayad was inspired by an impassioned desire to know and to understand. This was no doubt primarily a wish to understand and know himself, to understand where he himself stood, because he was in the impossible position of a foreigner who was both perfectly integrated and often completely inassimilable. As a foreigner, or in other words a member of that privileged category to which real immigrants will never have access and which can, in the best of cases, enjoy all the advantages that come from having two nationalities, two languages, two homelands and two cultures, and being driven by both emotional and intellectual concerns, he constantly sought to draw closer to the true immigrants, and to find, in the explanations that science allowed him to discover, the principle of a solidarity of the heart that became ever more complete as the years went by.

This solidarity with the most disadvantaged, which explains his formidable epistemological lucidity, allowed him to demolish and destroy in passing, and without seeming to touch upon them, many discourses and representations – both commonplace and learned – concerning immigrants. It allowed him to enter fully into the most complex of problems: that of the lies orchestrated by a collective bad faith, or that of the real illnesses of patients who have been cured in the medical sense, in the same way that he could enter a family or house he did not know as though he were a regular and considerate visitor who was immediately loved and respected. It allowed him to find the words, and the right tone, to speak of experiences that are as contradictory as the social conditions that produced them, and to analyse them by mobilizing both the theoretical resources of traditional Kabyle culture, as redefined by ethnological work (thanks to notions such as elghorba, or the opposition between thaymats and thadjjaddith), and the conceptual resources of an integrated research team from which he was able to obtain the most extraordinary findings about the most unexpected objects.

All these virtues, which the textbooks on methodology never discuss, his incomparable theoretical and technical sophistication, and his intimate knowledge of the Berber tradition and language, proved indispensable when it came to dealing with objects which, like the so-called problems of ‘immigration’, cannot be left to the first person who comes along. Epistemological principles and methodological precepts are, in this case, of little help unless they can be based upon more profound discourses that are, to some extent, bound up with both experience and a social trajectory. And it is clear that there were many reasons why Abdelmalek Sayad could see from the outset what had escaped all other observers before him. Because analysts approach ‘immigration’ – the word says it all – from the point of view of the host society, which looks at the ‘immigrant’ problem only insofar as ‘immigrants’ cause it problems, they in effect fail to ask themselves about the diversity of causes and reasons that may have determined the departures and oriented the diversity of the trajectories. As a first step towards breaking with this unconscious ethnocentrism, he restores to ‘immigrants’, who are also ‘emigrants’, their origin and all the particularities that are associated with it. It is those particularities that explain many of the differences that can be seen in their later destinies. In an article published in 1975, in other words long before ‘immigration’ became part of the public debate, he tore apart the veil of illusions that concealed the ‘immigrant’ condition and dispelled the reassuring myth of the imported worker who, once he has accumulated his nest egg, will go back to his own country to make way for another worker. But above all, by looking closely at the tiniest and most intimate details of the condition of ‘immigrants’, by taking us into the heart of the constituent contradictions of an impossible and inevitable life by evoking the innocent lies that help to reproduce illusions about the land of exile, he paints with small touches a striking portrait of these ‘displaced persons’ who have no appropriate place in social space and no set place in social classifications. In the hands of such an analyst, the immigrant functions as an extraordinary tool for analysing the most obscure regions of the unconscious.

Like Socrates as described by Plato, the immigrant is atopos, has no place, and is displaced and unclassifiable. The comparison is not simply intended to ennoble the immigrant by virtue of the reference. Neither citizen nor foreigner, not truly on the side of the Same nor really on the side of the Other, he exists within that ‘bastard’ place, of which Plato also speaks, on the frontier between being and social nonbeing. Displaced, in the sense of being incongruous and inopportune, he is a source of embarrassment. The difficulty we have in thinking about him – even in science, which often reproduces, without realizing it, the presuppositions and omissions of the official vision – simply recreates the embarrassment created by his burdensome nonexistence. Always in the wrong place, and now as out of place in his society of origin as he is in the host society, the immigrant obliges us to rethink completely the question of the legitimate foundations of citizenship and of relations between citizen and state, nation or nationality. Being absent both from his place of origin and his place of arrival, he forces us to rethink not only the instinctive rejection which, because it regards the state as an expression of the nation, justifies itself by claiming to base citizenship on a linguistic and cultural community (if not a racial community), but also the false assimilationist ‘generosity’ which, convinced that the state, armed with education, can produce the nation, may conceal a chauvinism of the universal....