Suche

Lesesoftware

Info / Kontakt

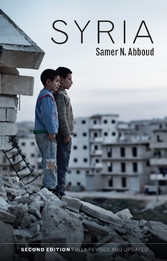

Syria - Hot Spots in Global Politics

von: Samer N. Abboud

Polity, 2018

ISBN: 9781509522446 , 304 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: DRM

Preis: 15,99 EUR

eBook anfordern

Introduction

When negotiations between the Syrian regime and some opposition groups began in Geneva in 2016, Mohammed Alloush, a commander of the armed Islamist group Jaysh al-Islam, was designated as lead negotiator for the opposition. Many Syrians and observers of the conflict, especially those who were captivated by the possibilities that the uprising created, would have been excused if they had to rub their eyes to make sure that they were witnessing reality. Alloush, who was told by regime negotiators that they would not talk to him “until he shaved his beard” (Wintour, 2016), was perhaps not the expected, let alone ideal, choice of Syrians who took to the streets en masse in 2011 demanding political change. That a leader of an Islamist armed group would have been the lead negotiator for the Syrian opposition is not an accident, of course; it is the outcome of years of struggle, betrayal, intervention, and profound violence, which shaped the trajectory of the Syrian conflict and its main protagonists. How did the Syrian revolution evolve this way? Why was Alloush chosen to lead peace negotiations? What happened to the revolution? What explains regime survival? The book that follows tries to capture this story and answer these questions about one of the most brutal conflicts in recent memory.

The daily lives of Syrians have changed dramatically since March 2011 when protests against the fifty-year rule of the Ba’ath Party began in the southern city of Dar’a. What began as a movement of sustained protest demanding regime change and political reforms has morphed into one of the most brutal and horrific conflicts in the post–World War II era. The conflict had evolved toward a political and military stalemate as all major domestic and regional subjugating actors aimed toward a decisive military solution—until a decisive military solution arrived in the form of Russian intervention that has moved the conflict from stalemate to what I call later in the book an “authoritarian peace.” In the context of this trajectory, the humanitarian crisis wrought by the conflict is worsening: more than half of the total population killed, maimed, or displaced within only six years. The human tragedy of the Syrian conflict has no current end in sight despite proclamations from regime loyalists and oppositionists that the conflict is nearing its military end. The damage has been wrought, and as we know from most conflicts what appears to be the end may simply be the beginning of something else equally catastrophic and violent. From the Syrian regime itself, which bears ultimate culpability and responsibility for the descent into maddening violence; to the various rebel groups; to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, and Iran, the inability to end the conflict has ushered in decades of future struggle for Syrians.

Telling the story of the Syrian conflict is a complicated endeavor, especially in a context in which popular understandings of Syria reduce the conflict to simple binaries (Sunni/Shi’a or regime/rebel) that misrepresent both the complexity of Syrian society and the conflict itself. In the pages that follow I attempt to confront these simplistic dichotomies and to introduce instead a broader picture of the Syrian conflict, one that moves back and forth between the meta-issues (such as regional rivalries, international involvement, and ideological and sectarian calculations) and the micro-issues (such as intra-rebel cooperation and conflict, the humanitarian crisis, and the administrative fragmentation of the country) that are shaping and driving the military and political dynamics of the conflict. A major theme throughout the book is how a military and political stalemate emerged and how the Russian intervention broke this, and what it may mean for the future of Syria. This is not to suggest in any way that the post-Russian intervention period is bringing the conflict to an end. I suggest instead that this is the latest stage in an evolving conflict that has many dynamics and subjugating actors. In introducing the dynamics driving the conflict I also answer questions about who the main actors are, including the Islamic State of Iraq and as-Sham (ISIS), whose rise and fall reflects broader trends in the complicated dynamics of the conflict, as well as the impossibilities of reaching a solution in the short term. One of my central goals is not only to trace the rise of groups like ISIS but to give insight into the constantly shifting nature of alliances among rebel groups, the issues driving the political elements of the conflict, and the main actors (both local and international) who are playing key roles in the conflict. The goals for this book are to help the reader understand the broader dynamics driving the conflict, why it has persisted, who the main actors are, and why it has evolved in the way that it has.

In the popular understanding of the Syrian conflict, it has morphed from a revolution into a civil war (see Hughes, 2014), but the conflict is not as linear as this suggests. There remains an active, robust, and committed movement of Syrians trying to rebuild their country, and to lead it free of the regime and the armed groups that now control it. They have become peripheral and rendered invisible by the profound violence inflicted on civilians and by the presence of so many armed groups, but they exist. Thus the Syrian conflict is more than an uprising that morphed into a civil war; it is a conflict with multiple dimensions that include, among other things, a revolutionary project to restructure society; an international effort to destroy Syria; war profiteers and criminals who fuel conflict; and regime loyalists, from within and outside Syria, intent on countering what they perceive as a conspiracy to overthrow the Assad regime.

Thus the Syrian conflict does not have a definitive beginning or a linear trajectory. What is at stake, analytically speaking, is the understanding of the parallel processes of revolution and civil war, as well as the antecedent processes of intervention and criminality, and their short- and long-term effects on Syrian state and society. This requires attentiveness to the nuances and complexities of the Syrian conflict that most popular understandings lack (Rawan and Imran, 2013). From my perspective, such attentiveness requires an examination of the interplay of many factors: historical analysis, political economy, the role of international actors, the structure of networks of violence, and so on. With this in mind, the story I tell in the pages below begins in the Ottoman era with the formation of a landed elite that controlled the political and economic levers of society right through to the Mandate period. In the post-Mandate period of independence, mobilization of the socially disaffected classes overthrew the pre-existing order. Out of the remnants emerged the Ba’ath Party, which has ruled Syria since 1963. The subsequent decades witnessed the consolidation of Ba’athist control of Syria and state institutions and the emergence of an authoritarian regime that ruled Syria through a combination of repression and clientelism. The lack of any sort of political freedoms, and the massive socioeconomic changes wrought in the 2000s by a shift away from socialist-era policies toward market-driven ones, fueled societal grievances that eventually propelled the protests that began in March 2011. The Syrian state and society have undergone three seismic shifts in the last century: the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Mandate period, and the era of Ba’athist authoritarianism.

Intersecting with this historical evolution are the social realities consequent on changes in the nature and structure of the Syrian state. The expansion of the state under the Mandate authorities fundamentally changed the relationship between state and citizen and brought the political authorities into the everyday lives of Syrians. Under the Ba’ath, the state was reoriented toward the dual goals of regime preservation and social mobilization through state institutions that would link different segments of Syrian society, especially those on the peripheries of Mandate politics, to the state and regime. The incorporation of new social actors transformed the material and political basis of Syria’s social stratification and brought to political power a regime that was dominated by leaders from Syria’s minority communities and rural areas. Ba’athist rule involved the distribution of social welfare in exchange for political quietism in Syria’s incorporated social forces. By the 1990s this model had exhausted itself, and the regime slowly turned toward the market. By the time the uprising began in 2011, Syria had undergone a decade of dramatic economic transformation that had ruptured the economic links between state and society established from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Syria played a major regional role during this period as well, having fought two wars with Israel (in 1967 and 1973) and then intervening in Lebanon’s civil war later in the 1970s. The Syrian presence in Lebanon lasted until 2005, when a series of protests led to the withdrawal of the Syrian troops and security personnel who had exercised control over the Lebanese political system after the end of the country’s civil war in 1991. The Middle East Peace Process in the early 1990s never realized a return of the occupied Golan Heights from Israel and a cold peace prevailed between the two countries up until today. Syria’s regional alliances shifted considerably in the decades prior to the uprising, with the regime supporting various Palestinian factions against one another, Kurdish separatist...