Suche

Lesesoftware

Info / Kontakt

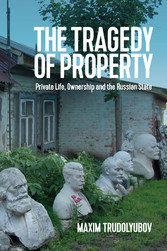

The Tragedy of Property - Private Life, Ownership and the Russian State

von: Maxim Trudolyubov

Polity, 2018

ISBN: 9781509527045 , 220 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: DRM

Preis: 17,99 EUR

eBook anfordern

INTRODUCTION

The Tragedy of Property

The enserfment and emancipation of the peasants, the Russian Revolution and collectivization, a massive residential building programme and, finally, the transfer of newly privatized apartments to their occupants are all landmarks in Russia’s history that have an impact on us today. They are all about land and the ownership of property, whether people are tied to the land or released from that tie; they are about the confiscation of property and the reacquiring of it.

These events affected literally every Russian. Tens of millions of people lost all they owned in the early 1930s; tens of millions had privacy returned to them as a result of residential building on a massive scale between the 1960s and the 1980s (see chapters 1, 10 and 11). Homo sovieticus was a product not so much of the revolution as of an acute housing shortage in the rapidly expanding cities. Character was formed and careers were made in cramped living conditions, through squabbles and friendships as neighbours battled over square metres of floor space. For millions of people in the USSR, possessing their own home was their ultimate dream.

The aspiration to privacy is an issue future generations will still have to address, but there has been a qualitative change affecting everyone in Russian society: the difficult transition from collective homelessness under the Soviet state to personal, private life has been achieved.

Giving its members a private life is a major step forward for any society. Today, the opportunity of being alone with yourself and your loved ones seems to us only natural. We feel that our four walls, our family affairs, our feelings and words belong to us alone; that is now not only an aspiration but a right enshrined in the constitution. In Russia, however, it is a very recent achievement, something that, in historical terms, happened only yesterday. Actually, it has not been around in the rest of the world for all that long.

Throughout history, human beings have existed primarily as a unit within a tribe, a group, a commune, an army, a guild, a community, a church. There has been no respite from need and want and pressure from their fellow humans. Humans may be social animals, but they value privacy.

For most of history only a privileged few, leaders and saints, have been able to withdraw into their shells. For the common man or woman, the path to a life apart has been long, arduous and slow, and it has come by way of the Industrial Revolution, the expansion of trade and the emergence of the middle class. The end result has been creation of the space essential for private life, the home exclusively for just a few people, immediate family. Before he could live in a separate apartment or house in a town, the working man who was neither a leader, a feudal lord nor a gangster boss had to rise above the threshold of hand-to-mouth living to become more ambitious and bring in more than subsistence wages. That became possible as he gradually escaped from a barrage of restrictions and as monopolies on trade and power were eroded. Geographical exploration, private ownership of land, new technologies and, with them, new ways of making money have all helped to promote the concept of private life (see chapter 3).

The acquisition of a home of your own would have been an impossibility in Russia without a new recognition of the importance, and the introduction on a massive scale, of the right to own private property. The sense of ownership of the place you live in goes back, no doubt, to the very beginnings of human culture, but awareness of one’s own personal identity and consolidating the boundaries of private life is even now a work in progress (see chapter 4). At the same time, agreement is developing on what an individual may or may not consider legally his or her own property.

In all cultures, including Western cultures, there have always been alternatives to private property, in the form of public and state-owned property. Many countries are seeing increasing adoption of forms of temporary or shared use of goods. Cars, apartments and second homes are often rented rather than purchased outright. It is a curious fact that in countries with the most venerable tradition of private property, the percentage of home owners among town dwellers is substantially lower than in Russia. In Switzerland it is less than 50%, in Germany it is just over, and in the United Kingdom it is around 68%, as against 85% in Russia.

In Russian culture, the various types of property ownership evolved differently. There is nothing mystical about that; it has nothing to do with the mysteries of the Russian soul, although it is just possible that a lack of freedom and the constraints on life in such a vast country bear some relation to the nature of our society and state.

In centuries past, Russia’s rulers extended their domains and exercised control over vast territories by centralizing power rather than negotiating and delegating it. The fact that the Russian state saw its main aims as territorial expansion and security inevitably affected the way society developed, and the predominance of such sources of wealth as furs, peasant labour, timber, grain and oil facilitated the emergence of a particular style of rule.

Its priorities emerged as the Muscovite state was taking shape, and they were the creation of robust defences against external enemies, and extraction of natural resources for the benefit of a small elite. Development of a professional bureaucracy and improvement of arrangements at district level were conspicuously sluggish, which suggests they were of little concern to that elite. There is a marked difference in the welfare and mood of citizens between countries whose leading figures interest themselves in improving social conditions and countries where they do not. The latter tend to be colonies, or otherwise states where the ruling elite are interested only in exporting natural resources and other goods (see chapters 5 and 6).

Russia is an odd country, because it is simultaneously a colony and a colonizer. The paradoxical outcome of its centuries-long expansion has been that, despite having a great deal of territory, it feels overcrowded; and it feels overcrowded because so little of its vast territory has been intelligently developed.

The fact that there exists one single, overriding source of easy money sets the ground rules. If these reward a particular type of behaviour, savvy players will adopt it. If one route for advancement is far more rewarding than any other, everybody will head in that direction: to St Petersburg, to Moscow, to the state treasury, to the decision-making centre. The extraordinary concentration of resources in the two capitals and neglect of the provinces are related: underdevelopent of the latter is the direct consequence of a strong, centralized regime. We have too little space because we have too much regime.

In Russia the universal human desire for personal well-being constantly collides with a political system that puts maintaining order (in terms of class, ideology and the state) above economic development. Unlike in the West, private property has not been a badge of citizenship, conferring rights and involvement in public affairs. The institution was not well regarded either before the Bolsheviks’ revolution or after the revolution of Yeltsin and Gaidar in the 1990s. For some, property was, and is, a legitimate means of retaining their dominant position, for others it was, and is, evidence of a profoundly unjust social system (see chapters 7 and 8).

Many scholars have linked the languishing of the institution of private property in Russia with peculiarities of the country’s political development. The best known examples are Richard Pipes’ Russia under the Old Regime and his Property and Freedom,1 in which he correlates the extent to which private property develops in Russia with the level of political freedoms.

There has, however, been no lack of private property in Russia: it has existed in one form or another throughout our history, and in the last 150 years of the St Petersburg period it was even more radically ‘private’ than many European analogues. The problem is just that property and freedom in Russia are entirely separate: they occupy parallel universes.

At one time it was customary in Anglo-American discourse to talk about the ‘tragedy of the commons’, which was held to show the impossibility of sharing resources equitably and to demonstrate the superiority of private property. In Russia, it seems to me, we need to talk rather about the ‘tragedy of private property’. The history of attitudes to property here is different from that of the West. In Russian political culture, private property has not provided a foundation for awareness of other civil rights. Those championing property and those championing human and civil rights have often been on opposite sides of the political divide. Private property, particularly large amounts of it, has been perceived in our culture as unearned and hence not deserving to be defended. It was used negligently and foolishly, with the result that society did not see it as having any great moral value and readily repudiated it during the social upheaval of the 1917 Revolution. ‘If private property was easily swept away in Russia, almost without resistance, by the whirlwind of socialist passions,’ S.L. Frank wrote in ‘Property and Socialism’, ‘that was simply because belief in the rightness of private property was so weak; even the robbed...