Suche

Lesesoftware

Info / Kontakt

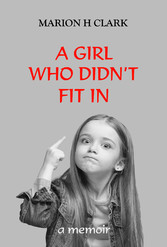

A Girl Who Didn't Fit In - Crushed by Gaslighting but not Defeated

von: Marion H Clark

BookBaby, 2020

ISBN: 9780646825663 , 262 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: frei

Preis: 9,51 EUR

eBook anfordern

Chapter 1

BEGINNINGS

As soon as we are born, our parents, extended family siblings

and others plus events write on the nature of who we are.

These all define us. anon

It is 1937, and a trio of women are seated on a well-used leather lounge suite in the sitting room of a Californian bungalow in East Oakleigh, an outer suburb of Melbourne. The place is dark, and heaviness is in the air. On the mantel of a dark brown, open wooden fireplace is a chiming clock flanked by two orange porcelain vases. On the left side is a framed verse by Adam Lindsay Gordon:

Life is mostly froth and bubble.

Two things stand like stone,

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own.

A large rug covers brown floorboards in the centre of the room and heavy maroon curtains frame leadlight windows covered with ecru lace curtains. Two large prints on the walls depict Biblical scenes, and a framed plaque of The Last Supper is above the open fireplace. A black framed poem about death and the afterlife by Lord Tennyson hangs on the wall that is the closest to the kitchen door:

Twilight and evening bell, and after that, the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

For tho' from out our bourne of Time and Place,

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crossed the bar.

My grandmother speaks, ‘You shouldn’t have tried to have a baby in the first place, Gerte.’

I agree’ says Elsie, her youngest daughter ‘You don’t know how to be a mother; you are just not capable. You should be ashamed of yourself for wanting a child. It’s for the best that you lost this baby and the first one as well.’

Gerte is tearful, ‘The lady at the hospital wasn’t kind to me’, she says, ‘I shouldn’t have told them that I own my home. When she found that out, she told me that I had no business being there because that hospital is for poor people, not me. She knew that I was four months pregnant and losing a lot of blood, so I asked her what I should do. She told me to go back home. I couldn’t understand why she was refusing to help me because when I lost the first baby, they admitted me to that hospital and gave me a curette. That’s why I went back there.’

‘I think it’s all for the best’ says her mother.

Elsie agreed nodding, and says, ‘You will just have to get over it and get on with your life, after all, you will soon be 40, and that’s far too old for a woman to have a child.’

‘You have both had children,’ Gerte said accusingly, her mouth pursed and eyes steadily directed towards Elsie’s face, ‘Ron is 14 years old now. You’ve done all right bringing him up, and I could do the same.’

Elsie scoffs, ‘I know how to be a mother. I knew how to be a mother when I was 18, all you cared about when you were that age was about doing your crochet and fancy work to get money to top up your wages from the shoe factory so you could build this house, and what’s more, buy a car. What kind of example would all that be to a child? Have pity on it.’

My mother leaves the room, and noises from the kitchen suggest that she is preparing afternoon tea.

In many respects, my mother belonged to the Feminism era of the 1970s when women were burning their bras and asserting their rights as human beings to have the same rights as men. She was not interested in fashion or status, cut her own hair, made her clothes and didn’t wear a bra. She didn’t bake cakes, preserve fruit or make jam. She mended clothes, darned socks and painted walls. It was not unusual for her to re-tile chipped hearths, replace benchtops and repair a leaking roof. I watched her do the latter when she was 88 years old, holding my breath lest she falls.

My Nanna and Aunt Elsie were of the housewife kind, keeping the home fires burning and good food on the table. They both did it well with a great deal of well-deserved pride, and each believed that her way of doing things was the right way.

My Aunt, married to Walter, knew that her job was to look after her husband, the breadwinner. She knew her place: her washing was white; her cupboards were tidy and her house clean. She was in charge of the poultry pens and the vegetable garden.

Elsie and husband Walter lived in Emerald, a village in the Dandenong Ranges close to Melbourne. She had her routines: there was washing day, then housework day, sewing afternoons, baking days and gardening. He gave her the wages he received from his job as a slaughter-man for a local butcher every Thursday night. She counted the money and placed set amounts in labelled tins on the mantlepiece above the stove—one each for rent, groceries, electricity, wood and insurance. She then returned a small sum to him, his tobacco allowance. Elsie supplemented his income by selling eggs and dressed poultry to townsfolk and taking in house guests for short holidays during summer months.

Elsie liked to be out and about and considered herself to be stylish. She wore make-up, had her hair permed, smoked and drank alcohol. She was a relatively care-free woman and enjoyed life and gossiping at the local shops. Her weekends were for tennis and relaxation. She played the organ each Sunday morning at the local Anglican church and visits with friends were a priority.

Often tea was taken on Sunday afternoons at the homes of various women with bone china cups and homemade food provided by each guest laid out on a handmade lace cloth. Whether the occasion was at my Aunt’s home or one of her friends, there was always her pièce de résistance, a cream sponge which she placed with a measure of aplomb in the centre of the table. The glories and shortcomings of her offering was always discussed; this one was a little dry the oven must have been too hot; or, the eggs were too fresh this time. Nevertheless, the verdict was always the same: It was the best-baked cream sponge that the town had ever produced.

The conversation was always lively, and I can only imagine the gossip and Elsie being the star of the show. She was a gifted storyteller and could hold an audience for hours.

My Aunt speaks, ‘I always knew that Jean’s baby had something wrong with it; her pregnancy didn’t look right. I wasn’t surprised when I heard that it was stillborn.’

‘I heard that you were the one who found Mrs Miller dead on the floor last week’, said one of the ladies inviting a story.

‘Yes, that was me, and a shock it was too. I had baked biscuits and thought she would like a few, she doesn’t do much baking, you know. She didn’t answer the door, so I gave it a hard push, and it opened. When I got into the kitchen there she was, laying on the floor. I was very shaken up I was.’

‘Oh Elsie, that was terrible, what did you do?’

‘I could see straight away that she was dead so I ran over to the phone at the post office and rang Dr Jorgensen in Belgrave, I knew that he would know what to do. He told me to leave the matter to him, and I went home.’ ‘Poor May Miller’ said Elsie tearing up ‘She was a nice old soul, and to think that her laggard daughter turned her back on her. Disgusting! I liked May a lot, she was a good woman.’

Perhaps my Aunt’s spiciest stories concerned Rev. Charles Clark, the Anglican clergyman, whom my Aunt referred to as Old man Clark. ‘He had it on with the women you know. I feel sorry for his wife; she is a proper lady, very refined. He leaves her to bring up the children while he is out and about promoting himself. All parson’s do the same thing. I could tell you a few stories about him that would make your hair curl, believe me!’

My mother represented a clash of cultures that was beyond the understanding of her mother and sister. I have no doubt that they loved her, but she was an enigma that they couldn’t explain, and they both resented that one of their own didn’t fit in. She was a loner, bookish and considered ‘old-fashioned’ in her choice of clothes. She was not interested in hosting a lady’s afternoon with homemade cakes, and she didn’t gossip. They were correct about one thing though, my mother was not an earth-mother soft, comforting and tender as shall be revealed.

To know my mother, one needs to understand her sense of shame and humiliation about the turbulence of her parent’s relationship and the straitened circumstances of the family after her father left it.

Her mother, Helen Laura Foley, the 5th child of Thomas Foley and Elizabeth Stamp, was born on Christmas Day in 1868 at Donnelly’s Creek on the Walhalla Goldfields in Gippsland, Victoria. Thomas was the son of a convict, Ann Foley who was convicted at the Old Bailey in 1843 for stealing eleven pounds of pork from a shop in East London owned by a Mr Harrod, and sentenced to seven years detention in Van Diemen’s Land. She arrived with Thomas, then aged three years, on the women’s convict ship, Woodbridge, in Hobart on Christmas Day of that year. She was sent to the Female Factory and Thomas to the orphanage.

Helen’s mother, Elizabeth Rebecca Stamp married Thomas at Sale, Victoria in 1860 and in 1865 they were lured to Gippsland in search of gold. The couple with their three eldest children took up residence on the Crinoline Reef at Donnelly’s Creek not far from Walhalla. It was a brave move, but Elizabeth was a resilient woman having migrated to Australia alone after securing a position as a nursemaid in Melbourne before the...