Suche

Lesesoftware

Info / Kontakt

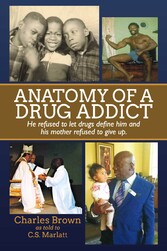

Anatomy of A Drug Addict - He refused to let drugs define him and his mother's refused to give up.

von: Charles Brown, C.S. Marlatt

BookBaby, 2020

ISBN: 9781098332938 , 274 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: DRM

Preis: 11,89 EUR

eBook anfordern

Mehr zum Inhalt

Anatomy of A Drug Addict - He refused to let drugs define him and his mother's refused to give up.

Chapter One:

The Family

“Other things may change us, but we start and end with family.”

—Anthony Brandt

I was born on January 2, 1949, to Willie James and Hattie Mae Brown. My brother Herbert was two years older than me, but it wasn’t until many years later that I learned we had different fathers. Apparently, my mother had a relationship with someone else before she married my dad, and Herbert was born out of wedlock. By the time I came into the picture she was living full steam for Jesus. As time passed, she tried her best to make sure all of us kids spent enough time in church to avoid making that same kind of mistake later in life.

I grew up with my parents and my ten brothers and sisters all living on Jacksonville’s Eastside in a tiny, 600-square-foot house with only one bathroom. Ours was an open house, where you could see all the way to the back where the bathroom was when you first walked in the front door. The only separate room was my parent’s bedroom to the left of the main room, but even their door was usually left open, so that the house was basically one big open room. It was a common style back then for wood-frame houses built in our part of town. Many of them have since been torn down or condemned.

Like all of my brothers and sisters, I was born at home with the help of a midwife who was a part of our community. She delivered most of the children in our neighborhood right there in our own homes. That’s the way it was back then. Midwives were an important part of most Black communities in the South. In those days, hospitals below the Mason-Dixon Line were usually segregated.

First, there was Herbert Lewis Brown, the eldest of the siblings. He was born in 1947, and as I mentioned, he was really a half-brother. I didn’t know the full story until later on, but looking back now I can see that Herbert never really felt like he was a full-fledged member of the family. He was my mother’s son but not my father’s, though as far as I could tell my father treated him the same as the rest of us. Herbert died from esophageal cancer at sixty-eight after struggling for many years with what was clearly a family-wide addiction to drugs and alcohol.

I came in second in 1949, followed by my brother Willie James Brown, otherwise known as “Pumpkin.” He was born on March 25, 1950, and died in April of 1990 at the age of forty. Pumpkin became a heavy drug user and eventually was a dealer of some reputation in the Jacksonville area. He was killed by two crackheads who shot him because he wouldn’t give them some drugs on credit.

After Pumpkin was our sister Brenda, who came into the world in 1952. She died just a year later from pneumonia. I was only three at the time, and my memory of her is just what I was told over time by my mother, father, and other family and friends who had witnessed the short life she lived.

My sister Hazel was born in 1953 and was a real blessing to my mother. After losing Brenda to pneumonia and having had a miscarriage sometime between Herbert and me, my mother could probably see that raising a bunch of boys would have its challenges. When Hazel was born, I’m sure our mother saw having a little girl in the house as a gift from the Lord.

Clarence Mack Brown was next in line. He was born in 1955 and somehow ended up with the nickname “Bobe” (pronounced Bo-bee). For some reason Bobe tried to pattern his life after mine. He always wanted to be like me. In many ways we had a unique connection because our birthdays were just two days apart in the same month. I was born on January the second, and he was born on the fourth. As much as he wanted to follow in my footsteps, for some reason I would get away with things, and he would always get caught trying to emulate me in his behaviors. In fact, when our mother passed away in 1971, Bobe was in a juvenile detention home and had to be escorted to her deathbed by corrections officers. The same thing happened when our father died six years later. Bobe was in prison at Sumter Correctional Institution and had to be escorted to the funeral in handcuffs.

Bobe was always in trouble with the law. Though he was six years younger than me, he spent more time in prison than I did. I always felt like I needed to look after him because he was so much like me and was always trying to follow in my footsteps. I tried to take care of him when I could, but he was extremely independent, even at a young age, and refused my attempts to give him any guidance. Later in life I suffered tremendous guilt over the fact that I was the first one to stick a needle in his arm and introduce him to heroin. In 1997 I had a brain aneurism that put me in the hospital for a month, but I survived. Three years later Bobe died from a brain aneurism at the age of forty-five. Even in his death we were linked together in a very strange way.

Timothy Sumlin Brown was next in line, being born in 1956. Tim was one of the most independent people I ever knew. He always did what he wanted to do, and he did it the way he wanted to do it. In fact, he was the only Black redneck I was aware of. He enjoyed being with those kinds of guys, and he loved to drink and carry on like a backwoods country boy. From an early age he loved to drink, and after a few years of imbibing, he could drink a fifth of liquor every day and sometimes even more. He loved to tell jokes, and he was good at it. Everyone loved him because he was always the life of the party.

Tim was one of those guys who could fix anything. He was a born craftsman and made a good living as a handyman. Timothy rarely took life that seriously. He never got married and just seemed to live as if there was no tomorrow. In his early thirties Tim went into the Gateway alcohol and drug treatment program in Jacksonville. He got sober and became a mentor to others who entered the program. Tim went to AA meetings religiously for seven years and was making a good living fixing anything that needed fixing. Then one day on a whim he took a drink. Immediately it was like he had never quit drinking at all. Six months later, at the young age of forty, Timothy was dead. Once he got back on the bottle, he drank himself to the grave.

For many years after Tim’s death I carried a sense of guilt about his sad life because I had introduced him to drugs when he was just a young boy. He caught me smoking weed in the driveway one day, and I gave him some to keep him from telling our mother what I was doing.

Tim was followed by David Lavon Brown in 1958. In many ways David was like Timothy; he loved to tell jokes and had a good time making people laugh. The two of them were the jokesters in our family and always kept things fun for us around the house. I think David was a genius. I remember when my parents bought Hazel a little child’s piano for Christmas. David, who was just two or three years old, started picking out songs by ear. He was a fast learner and always seemed to be able to learn anything like it was nothing at all for him. But like Timothy, he struggled with long-term alcohol abuse and died at the age of forty from tongue cancer. Doctors told us alcohol had probably contributed to his cancer and his death at such an early age.

Our brother Emery was born in 1959. Emery was a challenging case who always had mental health issues and alcoholism during his lifetime. He had cataracts removed from his eyes when he was just five years old, and for most of his life he lived with our great-aunt Allie. My mother’s aunt Allie was a real blessing. She had moved to Jacksonville from Madison, Florida, as a young girl to help my uncle with his two daughters. She became a great help to my mother as well and took care of Emery for most of his life. When Emery was nineteen, he tried to rob a liquor store with a toy pistol and got arrested. When they realized he had mental problems, they dropped the charges and let him go. Later he went into the Job Corps and was sent to its Camp Breckenridge in northwest Kentucky. Emery was a heavy drinker and died in 2007 at the age of forty-eight.

Carey Eugene Brown was the last boy my mother had and was born in 1960.

Carey and I never got along that well, and I viewed him as sort of a whiner who was always sad about something. I sometimes called him the “weeping boy.” When my mother was carrying him, there were several deaths in the family. Her mother had just died, and the whole year was a sad time around the Brown household. Carey eventually became a heavy drinker throughout most of his adult life, and he died from pancreatic cancer, which the doctors said was probably brought on by his alcoholism.

The final child born to my mother was our little sister Doris. She was born in October of 1964, and I am sure she brought great relief to my mother and my sister Hazel. It must have been tough on both of them having so many boys to deal with every day. While helping to bring Doris into the world, the midwife saw something in my mother’s womb and told her that she needed to have it looked at, but she never did. This eventually became the cancer our mother died from seven years later.

My sisters Hazel and Doris are still living today. Thank God they never fell sway to the addictions that plagued the men in our family and took all but me to an early grave.

As I write these words, I am struck by the knowledge that, other than me, all of the men in my family died premature...