Suche

Lesesoftware

Info / Kontakt

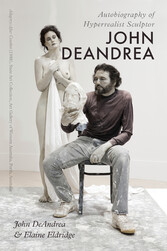

Autobiography of Hyperrealist Sculptor John DeAndrea

von: John DeAndrea, Elaine Eldridge

BookBaby, 2021

ISBN: 9781736213001 , 190 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: DRM

Preis: 11,89 EUR

eBook anfordern

1 LITTLE ITALY

You may wonder about my many nudes in quiet poses. It’s true I’m a man and I like looking at women, but after my childhood I wanted peaceful, and the young women who modeled for me, and the statues I made of them, were peaceful as well as beautiful. My childhood was anything but peaceful. Looking back, I’m a little shocked at all the things that happened to me.

The plaster ripped out all my hair when Bill pried the mold from my skin. The bacon grease I’d smeared on my body didn’t stop the plaster from sticking to me, but it must have helped a little, or the skin would’ve come off with the hair. It hurt like hell.

I had the idea to make a cast of my own body. I built a shallow wooden box outside the little house Bill and I rented and put sand in the bottom of it, like a kid’s sand box, and stretched out with my feet dangling over the edge. I put a rolled-up magazine in my mouth so I could breathe, and Bill poured 100 pounds of plaster over me. Pouring the plaster on my face just about killed him, but he did it. Except for my feet, I was completely covered. It was like being buried alive. No sound, no light, no breeze on my skin. The plaster took almost an hour to set. I wanted a perfect mold, so I didn’t move at all. Once the plaster started to set, of course, I couldn’t move.

At first the wet plaster was icy on my skin. But as it set, it got hot, hot enough to burn. My feet were sticking out so I could signal Bill. Wiggling my foot from side to side meant I was okay; up and down meant, “Get me out now!” When I could no longer stand the rapidly building heat, I moved my foot up and down as fast as I could. When Bill lifted up on the mold, I came with it, and he had to break the plaster in pieces to get me out. I’d worn a hair net to protect my head, but all the rest of the hair on my body where the plaster touched was torn out. I was badly swollen, and my face—I didn’t have a beard at the time—was a mess. Bill got me out before I was burned. The first thing I saw was his horrified expression. He wasn’t sure what he was going to find under the plaster. But Tiger, my Doberman, was happy. He tried eating the bacon-coated plaster, but he gave up pretty quickly.

Except for a mild case of shock, I was happy, too, because Bill didn’t completely destroy the mold when he released me. He was able to pry off one large piece that extended from my chin to partway down my thigh and included all of my chest and an arm. Later I poured the negative mold—the side of the mold that had touched my body and had all my hair sticking out of it—in plaster to get the positive mold I wanted. When I removed the positive mold, not just the shape of my body, but the hair and the pores on my skin, were reproduced perfectly. It was amazing. I couldn’t believe the detail I had captured. I had been hooked on the human figure since taking my first life drawing class in college. I wanted to make figures that were completely real, and this first attempt, even though I almost did myself in, convinced me I could succeed.

I wore shorts for this adventure in realism, by the way. I’m crazy, not masochistic.

Bill Leavitt and I lived near the Flatirons, part of the foothills that rise abruptly on the west side of Boulder. We were art students at the University of Colorado. After I graduated I took that mold back to Denver with me, but I lost it about a year later when I threw out all my work from college. I was prolific. I had hundreds of drawings and almost seventy-five paintings, most of them around 8 × 8 or 8 × 7 feet, stacked in my parents’ garage. There were so many drawings I tied them together with string in bales. I’m not sure what happened. I was angry a lot in those days, and the lack of respect at home made me mad. I was beginning to see myself as an artist, but no one in my family did. Even Mike, my favorite cousin, thought I was nuts. In Little Italy, the part of north Denver where I grew up, an Italian guy like me couldn’t just announce he was an artist and expect to be taken seriously. Real artists were Italian guys like da Vinci or Michelangelo—really important and dead for a long time. Anyway, I gathered all the paintings and drawings, all my work, borrowed a truck, and dropped them at the dump.

I think part of the trouble I had as a young man, being chronically angry and arguing too much, was thinking I should be like my dad. My dad used to shout when he was angry, which you could count on like the sun coming up. I was fortunate as a boy to know men who weren’t violent and angry, but it was always my dad who was most important, no matter what he did to me. He didn’t like me much. I can only remember one time, maybe two, when he seemed proud of me. The first was when he organized my doubleheader with the two Tommys after they sat on me in the street and poured dirt in my hair. I complained to my father when he got home from work, and he said, “Call those guys out.” So I rounded them up. Tommy One was at least a year older than me, and Tommy Two was two years older. I was the little guy, five years old. My father said, “Okay, you’re gonna fight, one at a time.” So I got myself together, and I fought Tommy One. He hit me and I hit him, back and forth, punch, punch, punch, and I think I won. I made him back up the hill, and my father said that fight was over. Then my dad called the other Tommy, and I fought, or tried to fight, him. The age difference gave Tommy Two a huge advantage. He slugged me as hard as he could. I got a few hits in, but the outcome was obvious from the start. Finally my father said, “That’s enough. You’ve had your fight.” Then he gave me all the change he had in his pocket and said, “This is for you. You did a really good job.”

I think he hoped, in spite of my disappointing tendency to take after my mother, that I may yet turn into a proper Italian son. He was a coward himself, but he knew I should be able to fight back if someone gave me trouble. He was right. In Little Italy, the part of north Denver where I grew up, you needed to know how to fight.

Imagine the stink parents would raise today if some other kid’s father arranged a fistfight!

The only other time he seemed proud of me was when a policeman brought me home after I’d been caught stealing two knives. I was eleven. Someone had stolen my pigeons. I found them penned up not far from our house, and I needed a knife (the second knife was for a friend) to cut the wire so I could retrieve them. The store owner caught me and called the police. I gave the owner a false name, of course, but the policeman who came pried my name and address out of me. My father didn’t say anything about my stealing and having a cop turn up at the house. He seemed, secretly and quietly, pleased with my escapade.

Other than those two times, I can’t remember my dad ever thinking I was any good. He rarely bothered telling me I was worthless. He showed his lack of approval rather than talking about it. The first physical violence I remember happened when I was four. Until then my dad was my hero. He wasn’t around much when I was little. He took out-of-state jobs, like ironworking in Salt Lake City, and was away for weeks at a time. I was thrilled when he came home. Just being with him made me happy.

For Christmas that year I got a cap pistol. I went to play with the younger Tommy—we remained friends for years, even after he poured dirt in my hair—who took it apart. I ran home holding the pieces, sure my dad could reassemble it. But he had a strange look on his face when he saw the pieces in my hands. I didn’t understand what was wrong. You’d think I’d burned the house down rather than broken a cheap toy. He started shouting, crossed the room quickly, and knocked my hat off. And then, in one smooth motion, he bent down, grabbed one of my boots in each hand, and flipped me upside down as he straightened, arms extended. The walls and table rushed past as I swung through the air. My feet slipped from the boots and I dropped headfirst on the floor. I didn’t cry.

His later violence was far worse, but at the time it was the worst beating I could imagine. I had a knot on the top of my head where it hit the floor. But more than pain, what I remember was my shock at his betrayal.

I never hated him for what he did. Not just dropping me on my head, but all the later beatings. If you didn’t grow up with a violent parent, or even if you did, you may find this odd. It’s hard to explain. He was my father. He was a snake. He was an untrustworthy snake, but he was my snake. For a few months when I was fourteen I wanted to kill him, but other than that I tried to love him, and I wanted him to love me. But even at four years old I somehow knew to stop trusting him. There’s a difference between not trusting someone and hating him. You can cope with not trusting someone. You can’t get around hating a person.

My father was the golden boy in his family, the chosen one who could do no wrong. The story was that he didn’t speak a word till he was five years old, not because he was slow to learn (my dad was anything but slow), but because all his older siblings did everything for him and he didn’t need to bother talking. When he wasn’t shouting or sleeping, the man I knew talked nonstop, presumably to make up for lost time. One time in high school I went deer hunting with him. We were gone about four days. He never stopped talking. On the way home, so help me god, I almost jumped from the moving car to get away from his voice.

When he was angry he’d carry on about being tied down with too many children and what...